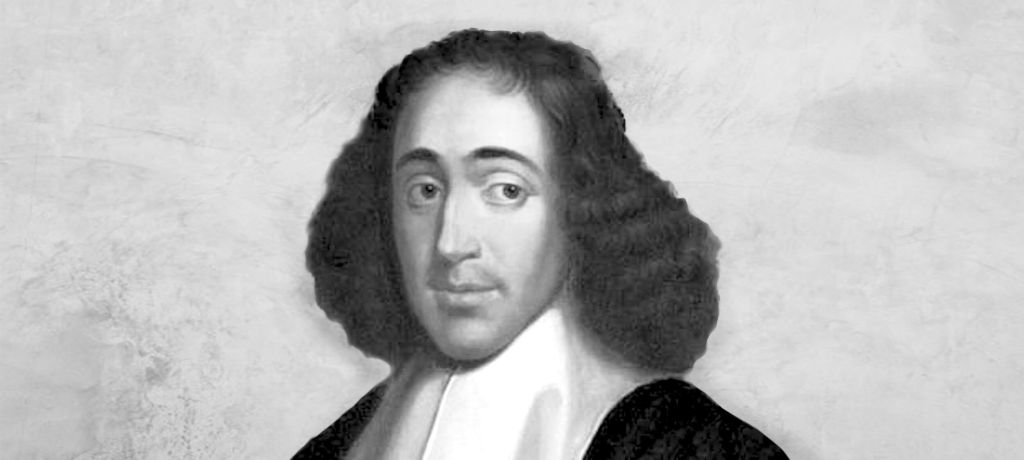

In his book, Tractatus Theologico Politicus (Tractate on Theology and Politics), Baruch Spinoza (1632-1677 CE), later Bennedictus Spinoza, argues for a rationalist view of religion. Spinoza was the descendant of Jews forced to relocate to the Netherlands from Spain or Portugal. He studied with several Rabbis in Jewish schools in his youth, including with a leading Kabbalist. He soon abandoned Rabbinical Judaism and Kabbalistic lunacy for a more rationalist approach to religious thought. The result was that he was estranged from the Jewish community. A document exists today which purports to be a writ of excommunication intended to exclude Spinoza from the Dutch Jewish community. There is some controversy over this document, as it may be a forgery. There is not really a formal process for the excommunication of a Jew from his or her community, so this was an extraordinary act. What is known for certain is that he ceased to be associated with the Jewish community.

While Spinoza clearly familiarized himself with Christian thought there is likewise no evidence that he ever took up Christianity in any form. In fact, while he pays respect to Christian thought in his works, he basically deconstructs the entire religion rationally. Spinoza leaves only one core Christian concept remaining and it is one entirely compatible with Judaism: to be a good and kind person who does the right thing. Within Judaism a debate has long raged betwixt scholars and schools of thought as to whether Hashem (G-d) is satisfied with a Jew who merely follows the laws and edicts of Torah or whether He requires us to be good and decent people; a force for good in the world. Spinoza boils Christianity down (removing Roman, Greek, and other dogmatic overburden) to falling to one side of that debate internal to Judaism: one must be a good and decent person; a force for good in the world.

This is juxtaposed with the notion held by some Jews that observing the law is an end unto itself and it doesn’t really matter whether one is a good or decent person so long as they follow Rabbinical tradition. This is a hotly contested notion in Judaism in general with strong camps favoring either approach. From the Rambam (Maimonides) and several other great Rabbinical scholars, we find frequent exhortations to be good people and do the right thing going far above and beyond the call of the law. The Rambam, for example, argues that the commandment not to “lead the blind man astray” establishes that we must not lead the ignorant astray either (whether Jew or non-Jew). Thus, Spinoza comes down fervently on this side of the debate and compliments Christianity for its emphasis on human decency and kindness in addition to basic morality.

Obviously, to be law abiding is an essential baseline for observance, since murder, adultery, and theft are obviously unkind. But that is only the beginning of following Hashem’s path, what I call “the Path of Righteousness.” This involves growing as a person to be more complete and confident in oneself, more knowledgable, and yes kinder and more loving. In an ideal instance, a righteous individual would be a good example to others, supportive and kind, leaving a positive and inspiring impression on others, while being true to honesty and mental health. Enabling others to break the law, be wicked, or to harm themselves and others would not be righteous.

Spinoza’s primary point hinges on the idea that while religious learning offers an important start to knowledge, reason is a separate and equally worthy pursuit. Essentially, the revelation of the Torah was the beginning of enlightenment and forms the basis for human conduct. Reason is also a form of revelation equal to the former, which builds upon the moral laws and calls for human decency to expand objective human knowledge. Hashem (G-d) taught our ancestors the law and sent them prophets to educate them (and, by extension, us) on how to be law abiding and civilized people.

There is a common Jewish aphorism that “Hashem also gave us minds that we can think,” which is used to dismiss especially literal or strange traditions or ideas that if implemented might be harmful or unduly difficult for a given community. Reason is a method by which the mind can develop objective and empirical conclusions by use of mental faculties. The ability to reason and use mathematical logic leads us to modern science and observable truth. Revealed truth and observable truth are thus equally valuable. Each represents the study of Hashem’s Laws. The Torah represents His basic moral laws for man, and reason and science pursues an understanding of His natural laws. Reason is also a gift from Hashem and it offers us a path to still greater rewards. Reason is open ended, able to expand and reach out universally to touch on any and all subjects.

Spinoza notes that the Torah promises only temporal rewards, seeking the establishment of an independent state in a particular piece of land wherein the nation will prosper. The Covenant (or contract) between Yakov (Jacob) and Hashem promised protection, a land (and state) in which to live, and general prosperity in exchange for dutifulness to Hashem. Reason offers far greater rewards and greater universally. The Torah focuses on obedience to Hashem and His law, such that people will be decent with one another at a basic level. Reason frees men from the need for such thorough obedience. Spinoza goes on to argue that if each person learns to reason, he or she can take greater responsibility for their own actions. They will no longer need to be coerced into sound behavior by the threat of punishment but will be drawn to it by the light of reason, a light that also shines from Hashem.

Spinoza lived in 17th Century and died in a time long before the events of the 20th Century. He was not aware that people would later “reason” themselves into committing the most egregious atrocities due to ideological biases. Were he aware of this, perhaps he might have placed greater emphasis on the Torah and the moral laws. I tend to disagree with Spinoza in his dismissal of these laws on that basis. If we are compelled to believe life is sacred and unjustified killing is a crime, such that we punish severely those who commit this crime, there can be no Holocaust, Holodormor, or the mass deaths under various socialist dictators. What Spinoza, among many other intellectuals, failed to recognize is that people often fail to distinguish between reason and rationalization. The moral boundaries of Torah provide us with absolute lines that cannot be crossed, even when we are tempted to rationalize wrongdoing to fit our personal desires or interests. While I am forced to disagree with his dismissal of the Torah and the traditions built around it, I generally agree that Reason is a powerful form of revelation and the objective truths discovered based upon it are incredibly valuable in our pursuit of spiritual enlightenment, and the combination of the two even more so.

In an eagerness to seek out supernatural miracles, for example, people too quickly dismiss the miraculous nature of Hashem’s creation. The splitting of the atom and the conversion of matter into energy is an incredible and “miraculous” aspect of Hashem’s creation. This was achieved due to reason, science, and the pursuit of the objective truths of Hashem’s natural laws. Likewise, with the ability to cure illness, to preserve and extend life like never before, and create modern comforts. Should these miracles be dismissed? How can one awe in Hashem (as the Rambam exhorts us to do) while ignoring the beauty of His creation? Should people die of preventable diseases? Should we live in the cold and the dark because we refuse the intellectual gifts Hashem granted us? I strongly believe we should not.

A Man Ahead of His Time

Spinoza is among the greatest minds Judaism has ever produced. A genius who lived long before his time. Spinoza’s thoughts on political structures foreshadowed democratic-republicanism, an idea that would begin to be experimented with for the first time in the late 18th Century in the United States; about a century after Spinoza’s death. Democratic-republicanism would rise forcefully in the 19th Century in the United States and Great Britain. The 20th Century would see it become the dominant political philosophy in the world, where it continues to reign supreme in the 21st Century. Spinoza’s notions of religious rationalism expressed in Tractatus Theologico Politicus and also in his Ethics are nothing short of brilliant. He is critical of the dogmas and bigotry that are built up (falsely) from the scriptures while extolling everything good and righteous in them. His commentaries on the structure, origins, and nature of the scriptures (including the Christian scriptures) are nothing short of awe inspiring. Indeed, he described in detail many of the same conclusions I had reached in general terms over the years of my own study, prior to reading his works.

If I have any criticisms of Spinoza, they are but few in number. Obviously, Spinoza was a man who had a time and place. No one is perfect and everyone makes errors. The greatest error Spinoza makes, which I described above, is the idea that those among the intellectual elites, who can reason, do not need ritual or traditions to live good lives, because they can be guided by the light of Reason. Spinoza could not conceive of how anyone guided by Reason could lose their moral compass. I believe men of reason need laws and traditions to guide them as much as those who are of simple mind. My experience of life has born this out.

Everyone needs externally imposed boundaries, guidelines, and laws to ensure that they do not act immorally. It is so easy for an intelligent person to excuse horrors or rationalize evil actions. Only when we know that murder is always immoral, that theft is wrong, and that each person’s possessions and dignity (let alone their bodies) must be respected, can we truly seek out the light of reason. The Path of Righteousness that leads to true Enlightenment (in a Jewish context) begins with the Torah, Neviim, and Kethuvim (the Law of Moses, Prophets, and Writings that make up the Hebrew Bible). From a mastery of the moral lessons contained within, one can then pursue the light of reason observing always the boundaries established by Hashem and our predecessors in the nation of Israel (the Jewish People). This was the path set forth by the greatest Karaite scholar Hakham Jakub Al-Qirqisani (ca. 890-ca. 960). He argued that while Jews should study science and philosophy, they must first take for a given the revealed truth of the scriptures. In other words, do not let your mind outthink your moral compass. We should not study so as to become disbelievers and then become amoral.

I also believe the national identity of the Israelites (Jews) is essential. The laws and traditions of Judaism, its holidays, and ritual life, must be maintained in order to provide a basis for the moral pursuit of knowledge. Here I find myself in a mild disagreement with Spinoza. He had been estranged from his Jewish community and sought to be relevant to his time in Europe in general. He thus studied Christianity and pursued reason outside of the religious context in which I live. It is understandable how he chose this path, given his history. Yet, I find it to be erroneous. Nevertheless, it was valuable for him to take that path so he could better understand reason and thus teach those who followed him.

In his time, if he were estranged both from Judaism and Christianity, and spoke contrary to the national interests of his home country (the Netherlands) no one would ever have known of his works and he would have passed into obscurity. In fact, sadly much of his work remained obscure until rediscovered in the 19th Century when English and later American philosophers took up his works finding in them a conceptual basis for the nature of the societies that had, by that time, emerged in both nations. Will Durant, the greatest of American philosophers picked up his notions and took them to still greater heights.

Baruch Spinoza A Great Jewish Mind

In the end, Baruch Spinoza was one in a lineage of incredible Jewish thinkers who helped to guide and to advance the course of human knowledge, not just Jewish knowledge. Along with other great Jewish minds like Moshe Ben Maimon (Maimonides or the Rambam), Jakub Al-Qirqisani, Gracia Mendes Nasi, Moses Mendlssohn, Emma Lazarus, Louis Brandeis, Albert Einstein, Hedy Lamar, Richard Feynman, Gertrude Elion, Isaac Asimov, Rosalind Franklin, Ruth Bader Ginsburg, and Stanley Fischer; Spinoza offered the whole world the benefit of his intellect. While accessible to everyone, his ideas do still have their application within Judaism. If Jews continue to hold to Jewish law and tradition while also exploring what Reason has to offer us, we will be all the better for it. Baruch Spinoza was indeed a man far ahead of his time and what he had to offer to mankind was truly incredible. We are all blessed by his life and contributions.

2 thoughts on “Baruch Spinoza”