For a podcast discussion of this article please visit Truth2U. For the second part here.

The Talmud is often presented as representing an “oral Torah.” There is no such thing, Torah is purely written. The Talmud and its core the Mishnah, never claim to be an oral Torah. In truth, the core of Talmudic authority is built on an argument which commences from the Sanhedrin. The theory put forth by properly educated Rabbinical apologists is that the Sages who set forth the Mishnah, the core of the Talmud, were members of the Sanhedrin, or otherwise represented a school of thought from the Sanhedrin. Therefore, it follows, Talmudic Judaism is constructed upon a legitimate institution of Torah, and its laws are binding. In this article I will refute that argument. I must note that as Mishnah and Talmud are purported to be the result of the authority of this body, they cannot be cited as historical sources to verify the accuracy of the claim. That would be circular reasoning: I have authority because I claim to have authority and I offer my own word as evidence. Therefore, I will use only non-Rabbinical sources, as any Rabbinical source would prove self-serving (except to describe Rabbinical claims).

The origin of the Sanhedrin is based upon a passage in Bemidbar (Numbers) 11:16:

16 And YHVH said to Moshe: ‘Gather unto Me seventy men of the elders (זקנ – zaken) of Israel, whom you know to be the elders of the people, and officers over them; and bring them to the tent of meeting, that they may stand there with you.

17 And I will come down and speak with you there; and I will take of the wisdom which is with you, and will put it upon them; and they shall bear the burden of the people with you, that you bear it not yourself, alone.’

Later, during the episode with the Daughters of Zelophehad in Bemidbar 27:2 there is a list of those who were with Moshe during his proceedings.

And they stood before Moshe, and before Eleazar the Cohen, and before the princes (נשׂיאם nassim) and all the congregation, at the door of the tent of meeting…

Who are these princes cited in the latter verse? Rabbinical interpretations claim this to be evidence that these princes were the members of this Council of Elders. Yet, the text says it was the princes of the tribes and makes no specific mention of this council. Two very different words with very different meanings are used. Nevertheless, the two verses in chapter 11 (16 & 17 quoted above) indicate the existence of this council and indicate that it existed to help Moshe govern the people.

Hashem shared with these elders some small part of the wisdom and law-giving authority that He had given to Moshe, such that they could assist him as he grew into old age. We know very little else about that institution. There is no mention of such a body acting or existing from the death of Moshe forward, and no mention of any institution anything like this council existing for over a thousand years thereafter.

This is what the Mishnah, the core of the Talmud, says of the Sanhedrin, again cited only to define Rabbinical claims about the body. Tractate Sanhedrin, Chapter 1 states:

The Great (Sanhedrin) consisted of seventy-one, and the small of twenty-three. Whence do we deduce that the great council must be of seventy-one? From [Bem. 11:16]: “Gather unto me seventy men.” And add Moses, who was the head of them–hence seventy-one? And whence do we deduce that a small one, must be twenty-three? From [ibid. 25: 24-25]: “The congregation shall judge”; “And the congregation shall save.” We see that one congregation judges, and the other congregation saves-hence there are twenty; as a congregation consists of no less than ten persons, and this is deduced from [ibid. 24:27], “To this evil congregation,” which was of the ten spies, except Joshua and Caleb. And whence do we deduce that three more are needed? From [Shemot 23:2]: Thou shalt not follow a multitude to do evil”–from which we infer that you shall follow them to do good. But if so, why is it written at the end of the same verse, “Incline after the majority, to wrest judgment”? This means, the inclination to free the man must not be similar to the inclination to condemn; as to condemn a majority of two is needed, while to free, the majority of one suffices. And a court must not consist of an even number, as, if their opinion is halved, no verdict can be established; therefore one more must be added. Hence it is of twenty-three.

Here the Mishnaic Rabbis expose their occasionally weak powers of exegesis. The seventy elders were a council to assist Moshe. While text states that the elders are gathered to help him, Moshe was not a explicitly a member of this council, he presided over it; the Vice President presides over the United States Senate, casting a tie breaking vote, but is not a member of the Senate. Moshe was also a Levite and the presence of the Cohen Hagadol (High Priest) during hearings of this court suggests that after Moshe’s death the High Priest would assume the role as presiding officer, if this council was to continue at all. Here the text can be interpreted in several different ways. Suffice it to say that there was a council of seventy elders and a presiding officer. The number was thus seventy or seventy-one. It can also be argued that following Moshe, the presiding officer should be the Cohen Hagadol.

Note that the Torah never defines a congregation’s size, here the Mishnaic Sages diverge significantly from the text. The word congregation (עדה – edah) is used most frequently to refer to the entire congregation, although it could apply to smaller gatherings. A congregation is any two Israelites up to the entirety. The nonsensical conclusion that a congregation is ten men is taken from the episode of the spies sent to investigate the Holy Land, when ten spies gave a negative report. That combined with a tortured reading of Tehilah (Psalm) 82 led the Rabbis determine that ten men constitute a “congregation.” So we see the ridiculous expanded into the asinine when two congregations plus three men constitute a Sanhedrin Katan (small council). The example of the constitution of the Sahedrin Katan (which is entirely extra textual) is why the Mishnah cannot be granted the status of authoritative. So poor a set of interpretations does not warrant so great a degree of respect. While other interpretations are sound, the logic behind them can be flawed.

In Devarim (Deuteronomy) 34:10 we find out that there could never be a prophet like Moshe. Moshe’s death at the end of the Torah concludes the era of lawgiving. From then on the law was a fixed, written document. While its provisions remained open to some interpretation, and clearly traditions and practices could be developed under its authority by the institutions authorized to do so, the law was complete. Moshe was gone, and one could argue that the wisdom that Hashem had shared with him was gone as well. It is certainly worth noting that this council of elders is never again mentioned in the remaining scriptures.

The Shofet (Chieftain of the tribes) Devorah heard cases beneath a tree, and there is no mention of a council. When the case was made against the Tribe of Binyamin why was it not heard before this council? Shoftim (Judges) 20:1-2 describes representatives of all of the tribes gathering but makes no mention of a council of seventy or of any particular number. When Boaz wanted to confirm that the levirate marriage with Ruth was being done correctly he sought out the elders of his city. The Torah mentions hakhamim (wise men) and princes of the tribes indicating the role of Israelites of smaller groups, whether tribal, regional, in urban centres, or today’s congregations, in choosing men and women whom they respect to act as leaders.

Kings Shaul, David, and Shlomo sat as the highest judges in their time. When Tamar was abused during David’s reign (2 Shmuel 13) why did she and her defenders not go before this council of elders? This lot included David’s son Avsalom who sought to overthrow his father. How better to embarrass the King than to have his judgement called into question by the council? The Rabbis claim that the Sanhedrin had the power to chastise a king; if ever there was an opportunity to do so in a righteous cause, why not then?

During the reign of King Yossiyahu of Yehudah (Judah) the Torah scroll was discovered and brought forth by the Cohen Hagadol Hilkiyahu (2 Melekhim – Kings 22). In order to ascertain its authenticity the book was taken to the Prophetess Huldah. Not before a council? Would not this council, this high court, have been the perfect institution to establish the authenticity of the scroll? In fact, it is only after Huldah had confirmed the scroll’s authenticity that the King brought forth the elders of the tribes and the other authorities. Again, no specific mention of a particular council of elders.

Upon their return to the land, the sages who led the Jewish people wanted to set out a canon and provide new rules for the leadership of the community. Who provided this leadership? According to the written scriptures the Zadokite priests were running the show, together with the Levites who served them. This is no surprise given that the Prophet Yekhezkel (Ezekiel) endorsed the Zadokite priests on four occasions to lead the renewed Temple due to their faithfulness to Hashem (Yekhezkel 40:46, 43:19, 44:15, 48:11). Based upon what is written, it is institutions that are established in and authorized by the Torah that were exercising authority. The priesthood, for example, and the Prophets, who are likewise provided for in the Torah.

Rabbinical tradition, however, holds that at this time there was a Great Assembly (Knesset Hagadolah) of 120 members which sat as a court similar to the later Sanhedrin. No mention is ever made, even indirectly to such an institution in the written texts. If the Sanhedrin had existed and had all of the powers that the Rabbis ascribe to it, why did the Sanhedrin not take on this task? Why was this body not made up of seventy-one as the Mishnah states the Sanhedrin was constituted? The Rabbis later ascribed many innovations to this body including the Amidah prayer, the synagogue service, and the canonization of the Tanakh to this body; a body for which there is no scriptural evidence whatsoever. The prayers and innovations so ascribed are known to have been generated much later. There is a long Rabbinical tradition of ascribing modern innovations to ancient sources.

When one reads of the return, it is evident that those who returned were trying to assert the continuity of the Kingdom of Yehudah. They called themselves Yehudim (for the Kingdom not for the tribe), they claim to be descendants of those who were prominent in that kingdom, and they are reestablishing all of the institutions that had once existed. They claim to be the descendants of the kings, priests, scribes, and great ministers of the previous kingdom. There is still not mention of any descendants of a great “prince of the court” or chairman of the council of elders as the Rabbis describe. There is no mention of any council of elders having ever been an institution in the Kingdom of Yehudah.

There are references to gatherings of elders throughout the books of the Neviim (Prophets) and Kethuvim (Writings), but aside from the single reference in Bemidbar, quoted above, there is no mention of a “great council” of elders numbering either seventy or seventy-one. Representatives of the tribal elders gather on occasion to make decisions for the nation, at times certain tribes refuse to send representatives or cooperate. Nevertheless, it is a stretch to suggest that these gatherings for political or legislative purposes had anything to do with what was clearly established in Bemidbar to be a high court that would hear cases and assist Moshe. A more comprehensive listing of such references can be found here. In each case, we can see that the reference is to tribal or local elders, or to some meeting of representatives of each tribe’s elders. Even if we make the logical leap that these are references to the council of elders referred to in Bemidbar, and this would be quite a leap, it is evident that this was not a continuous body. Elders were called together on infrequent occasions to address particular matters. There is no evidence of a continuous body or council of elders acting as a court or legislative body.

Since there is no direct evidence anywhere in the scripture for existence of such a council outside of Bemidbar 11, a strong argument can be made based upon the p’shat, that is the plain meaning of the text, that this council was temporary in nature. The council of elders clearly disbanded upon Moshe’s death or shortly after entering the land. No such institution existed or functioned for over a thousand years thereafter. A textual critic, cynical of the Biblical narrative might even argue that these passages were inserted later, as they seem to be a non-sequitur. Obviously, those who believe the Torah to be of divine origin must dismiss such arguments; but they are worth hearing in any case.

The Successor Council

If a successor council were to be established, what would its authorities be? Who would appoint its members? Who would preside over it? This is an interesting area to explore. Given that the Cohen Hagadol (High Priest) was present during deliberations when Moshe chaired the council, it makes sense that he might have succeeded Moshe and presided over the original council. There could never be another man like Moshe (Devarim 34:10), therefore we should be cautious about trying to fill a position that he held. Since there will already be a Cohen Hagadol it is reasonable that he preside.

The question of appointment is wide open. Moshe originally chose the seventy elders, how would elders be chosen today? Certainly, we would desire to have the wisest and most well respected Jewish jurists on such a court. It would certainly need to represent all Jewish movements and should represent many different areas of knowledge and fields of expertise. Having knowledge of Torah in general is not enough, there must be several leaders knowledgeable of slaughter, experts in civil and criminal law, carpenters, doctors, and the list goes on. This could be done fairly democratically by a legislative body like the Israeli Knesset, or the council could simply be appointed by order of the King. Nevertheless, it must be comprised of those men (and women?) who are known to be held in the highest regard, who are highly respected, and who are the natural leaders of the people.

What jurisdiction would the court have? Moshe originally sat as the court for all of the people until he established the Sarim (administrative judges) to adjudicate lesser disputes, on the advice of his father-in-law (Shemot – Exodus 18). This council would thus sit as a supreme court of a kind hearing cases referred by or appealed from these lower courts. Could the council have a broader jurisdiction? The Torah provides for a priesthood who minister to Hashem and whose leadership we must accept in ritual life. There are references to the priests judging who is clean, administering the trial by ordeal for the alleged adulteress, and having authority in matters pertaining to the Temple and its management. Religious matters are thus their jurisdiction.

If the court were to adjudicate a religious case, that is, a case based upon the priestly statutes, it would be doing so in consequence of the priestly authority, it would not be exercising any authority over the priesthood or the priests themselves. It might be that a priest was accused of wrong doing and because of the complex particulars of the case it was removed from priestly authorities to the court, but this would have been a rare and uncommon occasion, and it lacks precedent. Yirmeyahu (Jeremiah) was tried in the courtyard of the Temple by the King’s ministers, the priests, and the prophets (chapter 26). Again, there is a reference to elders in verse 26:17 but once again it is simply elders in the land, not a specific council of elders and no number is given. These elders simply came to Yirmeyahu’s defense calling for his exoneration. The trial was essentially before the King and his ministers.

The Council could not stray from the ideology of the Zadokite priests, as it has no authority to do so. We know that these priests believed only in a written law; they did not expand the law far beyond it or accept extratextual practices or ideas. Through its various decisions, the council could expand upon the existing commandments issued in the Torah, offering greater detail. Would a slaughter be considered Kasher based solely upon whether the animal died by exsanguination after having the throat cut, or must the cut sever both arteries to the brain and the food and wind pipes? Is only one cut acceptable or can a second be made? Such details would certainly be offered by the priests, as the realms of sacrifice and cleanliness are their jurisdiction. But if a case arose from the practices of a shochet (slaughterer) or group thereof, might the court not render a decision on these precise details, whether they were properly observed, and by what standard might these questions be judged? Nevertheless, as cases are tried, certain details would emerge that would become authoritative precedent. The Council would thus encourage or foster traditions and practices by their decisions to make certain that the law is not violated. In this way, it would have just slightly more authority than that of America’s current Supreme Court.

The Torah includes an office of chieftain (Shofet) who leads and judges the people. It also provides for a King if the people desire one. The Neviim (books of history and the Prophets) mention on several occasions ministers, courtiers, hakhamim, and generals who served the King and enacted his will. In this we see that executive, administrative, and military affairs come under the authority of the executive, whether a Shofet or a King.

There are also hints in the Torah about local and legislative authorities. There are tribal and local councils of elders. While not spelled out precisely or clearly, it is evident that the Israelites had the right to establish administrative and legislative leaders or bodies at the tribal, regional, or local level. It is thus clear that legislative authority is separate from the judicial authority and is established locally or nationally in institutions of a very different nature and character from the Council of Elders. This authority was exercised by elders of cities and tribes, by Kings and their ministers, and at times by the Shofet, but not by a national council of elders.

The Rabbis claim that the Sanhedrin was a successor to the Council of Elders references in Bemidbar and hold that it was a judicial and legislative body. They claim that it could exercise authority over religious matters, legal matters, civil matters, and administrative matters; it could even rebuke the King! None of these authorities can be found for this council anywhere in the Torah even by the greatest stretch of the imagination.

Upon the death of Moshe the Torah became a closed, fixed document. Devarim 4:2 makes it clear that no new commandments may be added nor may those already recorded be subtracted. Ezra, the Zadokite priest and scribe, had the entire Torah read aloud to the people in a single morning (Nehemiah 8:3). The Torah was clearly a closed written document that could be read and easily understood in its entirety. No argument can be fielded based upon the text for the expansive authority the Rabbis ascribe to this council.

Even if the Sanhedrin was all the Rabbis claim it to be, neither the Sanhedrin nor any successor council nor any institution claiming authority under it could ever create a new commandment. There could never be a commandment purportedly from Hashem to wash one’s hands before eating bread, to light candles on Shabbat, or to light candles on a Channukiah. What is the basis for these Rabbinical innovations? For these additional commandments purported to be from Hashem? This is the natural result when the law is taken from a fixed, written condition and placed under the authority of men, who naturally seek to expand their own power and influence through the addition of new stipulations.

If not from the Torah, then from whence can this Sanhedrin find its origins?

Greek Courts

In Archaic Athens a court was established called the Areopagus (hill of Ares) named for the hill upon which it stood northwest of the Acropolis. This court was staffed by retired Archons, administrators, who served for life. These men came initially from an hereditary class of noblemen, but were eventually permitted from other classes. The court had authority over important legal cases, served as a constitutional court in cases of impeachment, exercised authority over religious matters, and at times exercised a legislative veto. It was essentially an upper house to the Boule (Assembly). The court waxed and waned in authority and prestige as its members gained or lost respect. Eventually, it declined to hearing only murder cases. Due to the court’s patriotism in opposing the Persian invasions, it was ascendant at the rise of the Macedonian Era.

Phillip II of Macedon would form a military alliance with the Greek city states in order to fend off the Persians. Before anyone knew what had happened, he had defeated the Persians and consolidated power in Greece as well. Phillip cemented his alliance with the Greeks by forming a Synedrion at Corinth. A Synedrion (sitting together) is a council that is established to act in an administrative, judicial, and legislative capacity on behalf of the King. Much like the Privy Councils of England’s Kings, this body was an extension of the King’s authority. As the Macedonians expanded their empire, they established local Synedria to govern specific regions, a Great Synedrion was formed to govern the entire empire on the King’s behalf. It is no coincidence that Sanhedrin is the Aramaic transliteration of Synedrion and that the powers ascribed to the “Great Sanhedrin” by the Rabbis are precisely those ascribed to the Great Synedrion of the Macedonians.

History of the Great Sanhedrin

Phillip II of Macedon was the father of Alexander the Great, who would go on to conquer Persia (including the Persian province of Judea) and would later march into India. Alexander’s conquests are foretold by the vision of Daniel (chapter 8). Upon Alexander’s death his empire divided into four kingdoms. One of these was the Kingdom of Seleucia centred in Antioch in modern Syria and Turkey; another was that of the Ptolemys centred in Alexandria, Egypt. The geopolitical struggles between these two kingdoms were fought largely in the Levant and are described in some detail in the later visions of Daniel up through the Maccabee Revolt (chapters 9-12). Eventually, Judea came under the control of the Seleucid King Antiochus IV Epiphanies, who declared himself a deity and demanded to be worshiped as such throughout his kingdom. When the Jews refused to worship him, he desecrated the Temple.

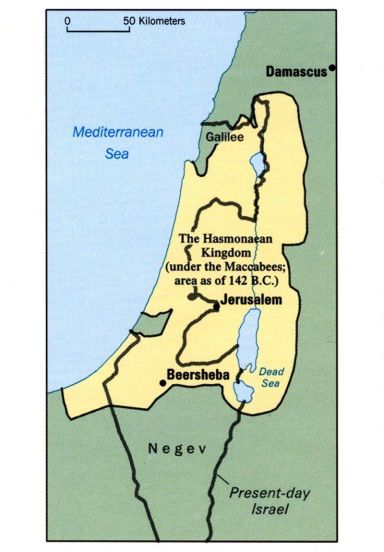

A Zadokite priest named Mattatiyah (Mattathias) rose up against the Seleucids. He and his four sons, would lead an army known by the acronym from which Maccabee is drawn. The Maccabees eventually defeated Antiochus, whose empire was overstretched. They founded the Hasmonean Dynasty in which the King was also the High Priest. It is not clear if a Synedrion had been established in Judea by the Macedonians prior to the Hasmoneans or if they created the institution themselves. The first historical reference to the body is in the works of the Jewish-Roman Historian Josephus. He makes the first reference to a “Gerusia” (council of elders) existing in the Hasmonean Kingdom during the reign of Alexander Jannaeus. Josephus first refers to a Synedrion in Judea later when the Roman Governor Aulus Gabinius established local governments in the region.

During the reign of Alexander Jannaeus (103-76 BCE), the Pharisees instigated a civil war. Jannaeus, as many Hasmonean rulers had been, was a Zadokite (Latinized: Sadducee) partisan. Eventually, the Pharisees collaborated with the Seleucids in their efforts to overthrow the king. Jannaeus executed many Pharisee leaders for their treachery. It was during this time that Josephus first mentioned the Gerusia (Council of Elders). Upon his death, Salome Alexandra succeeded Jannaeus, her late husband, and tried unsuccessfully to keep their two sons from warring amongst themselves. Hyrcanus II, the older son, and Aristobulus II struggled against one another for the throne. They were the last Hasmonean kings. The Roman general Pompey Magnus (Pompey The Great) arrived in Judea in 63 BCE in the midst of their quarreling; Judea became a Roman province.

Aulus Gabinius was named the governor of the region, began reorganizing the Judean government, and marginalized the priesthood. Josephus relates that Gabinius met delegations from the two competing brothers (Hyrcanus and Aristobulus) and a third delegation which opposed both (possibly the Pharisees). He chose the weaker Hyrcanus to remain high priest in name only, but substantially limited his power. The Jewish priesthood was thereafter a much weaker institution. Gabinius created five Synedria to govern the region. It is possible that a Great Synedrion was formed to provide regional leadership. Naturally, Gabinius and later Roman leaders would favour Greco-Roman institutions over less trustworthy Jewish ones, like the priesthood.

Is it possible that the Sanhedrin, so much beloved by today’s Rabbis, was established under the authority of a Roman governor? It is not clear if the Gerusia (council of elders) that Josephus refers to in the time of Alexander Jannaeus is essentially the same institution that was later called the Great Sanhedrin. It is more likely that the Great Sanhedrin was a new institution established by the Romans to secure their hegemony over the Jews. The Sanhedrin was at best a political and civil body with no religious authority under Jewish law. To argue that all Jews are bound by the decisions and interpretations of such a body would be like trying to claim that Judaism today is bound to the resolutions of the United Nations Security Council or the United States Congress, institutions with no authority under Jewish law.

Another matter upon which historians are not settled is the origins of the religious parties within Judaism at the time. Following the Maccabee Revolt the Essiy (Essenes) seem to have abandoned the cities for a communal country life, looking upon the institutions in Jerusalem as being corrupt. They sought a radical purification of the Temple, possibly even its total reconstruction. The Sadducees seem to be a latinization of Zadokite, the priestly party. By the time of the Maccabees, however, the Sadducees and the Hasmonean Dynasty were inextricable. It may be that much of what we read concerning the Sadducees are in fact references to the Hasmoneans and their partisans. Somehow a party called the Pharisees (from Paroshim – the separated) had formed around the same time. It is possible that these were more Persian-oriented Jews who rejected the Hellenization of the Hasmonean Dynasty.

The Karaite Jewish Hakham (wiseman) and Iranian scholar Jaqub Al-Qirqisani argued that the Pharisees gained strength by reaching out to the people directly. The Sadducees were well entrenched in power through the priesthood and the Hasmonean Kings. It is possible that many common people resented this and turned to the influence of the more populist Pharisees. Something like the Ashkenazic – Sephardic split today, the Pharisees may have perceived the Sadducees and Hasmoneans as an aggressive elite too interested in Greek ideas and too little interested in the common people. By the time of Roman conquest, however, all Jews were Hellenized, and the arguments against the Sadducees along these lines fall flat but may have remained as part of an ideological underpinning of the Pharisee party.

Between Josephus and the Christian books (in so far as they may be of use as historical records), it can be understood that the Pharisees had already begun to add to the written Torah in ways that would have been offensive to the Sadducees, and many Jews rightly dissented. There seems to have been at that time a Pharisee practice of washing hands before eating bread. This practice now includes a blessing claiming the practice to be commanded by Hashem, though no such commandment can be found in the written Torah nor can any authority be found to establish such a commandment.

It is certainly true that the Hasmoneans adopted a Hellenistic lifestyle, as did almost all of the peoples of the Mediterranean coast. They did, after all, establish a Greek style court to help govern their country. Jews in all times adopt the surrounding culture. Excavations of the priestly quarters in Jerusalem have found simple living spaces with all of the trappings of the Hellenistic lifestyle of the time from utensils to furniture, but no sign of Greek idols. There is no evidence that the Sadducees or Hasmoneans ever abandoned Judaism or Jewish practice. Why would they? Their power was drawn in significant part from the priesthood.

The Influence of the Sanhedrin Today

Following the destruction of the Temple, the institutions of Judaism collapsed. In the absence of the priesthood or any level of Jewish government, there were no legitimate institutions to lead the Jewish people. Since that time communities have had to rely upon their own recognizance for observance and leadership. The Mishnaic Rabbis, Pharisees to a man, may have been members of the Sanhedrin, or may represent schools of thought on the body. Upon what basis should such a body have binding religious and legal authority over all Jews for all history thereafter?

Rabbinical Judaism today claims that the Sanhedrin had supreme legislative, judicial, and religious authority in Judaism. They make the specious and virtually indefensible claim that this institution was based upon the Council of Elders mentioned in Bemidbar. They go on to assert that the institution continued to exist after the destruction of Jerusalem and the Temple and thus the Mishnaic Rabbis were a legitimate Sanhedrin (or otherwise represented schools of thought from that institution). It follows that the Mishnah and the Talmud (Bavli and Yerushalmi) and the later commentaries are authoritative and binding upon all Jews. Jews are not allowed to dissent. Yet, Jews have dissented, and despite numbers that shrank under Islamic control the Karaite Jews have existed as a movement for 1200 years, having coalesced from those congregations which never adopted the Talmud.

7 thoughts on “The Sanhedrin”