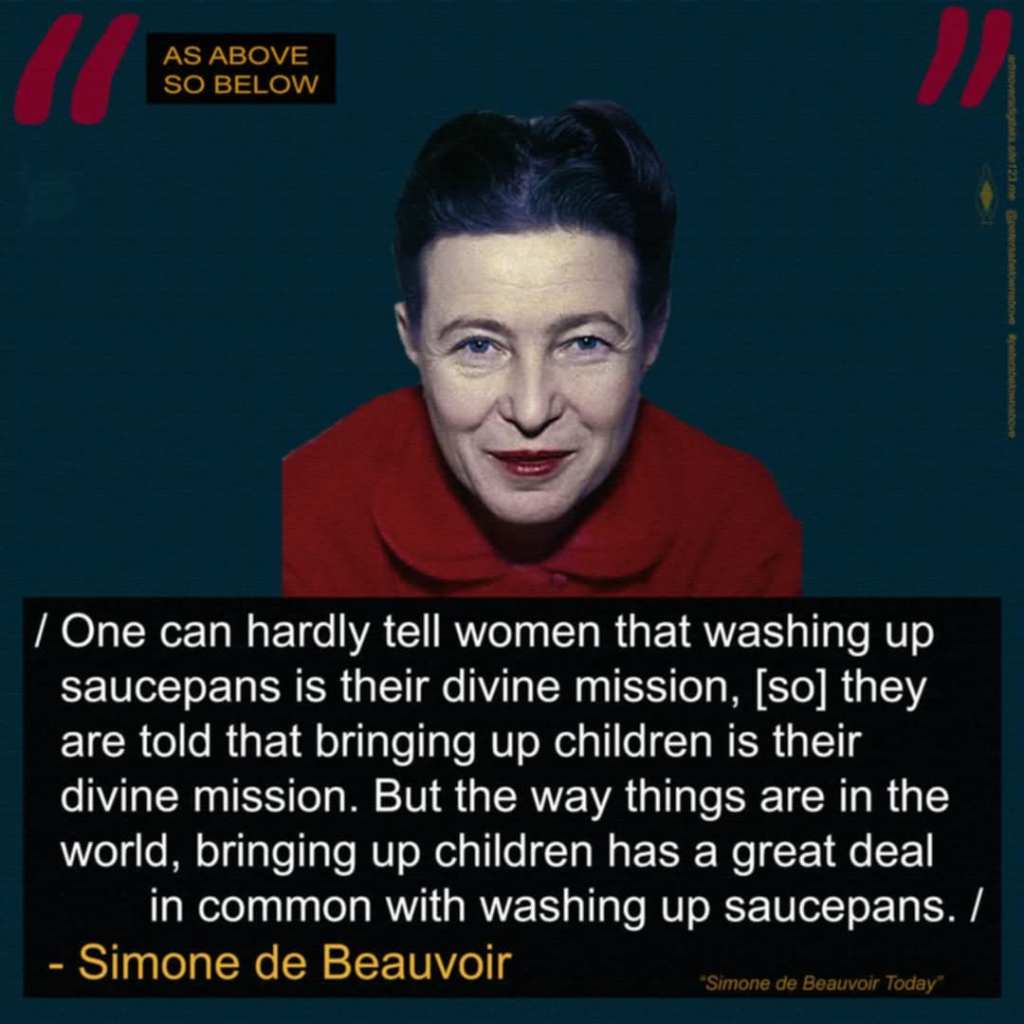

French feminist Simone de Beauvoir (1908-1986) once wrote, “One can hardly tell women that washing up saucepans is their divine mission, [so] they are told that bringing up children is their divine mission. But the way things are in the world, bringing up children has a great deal in common with washing up saucepans.” It’s a quote that recently popped up on my Facebook feed.

Now, Beauvoir and I disagree on many things, but I think this particular instance warrants some exploration. Simone de Beauvoir grew up in a French Catholic family, during the first half of the twentieth century. Her childhood was interrupted by World War I, during which her family struggled and she was sent to a convent school. In the aftermath, as a teen, Beauvoir became an atheist. She was noteworthy as ayoung woman for her academic achievement, being the youngest person ever and only the eighth woman to pass the postgraduate exams at the Ecole Normale Superieure, where she narrowly placed second to her future partner, Jean Paul Sartre. She went on to teach until 1943, her life being again interrupted before then by World War II. After that, she supported herself as a writer. Her academic and professional achievements, however, were set in a time when young women were still expected to secure their marriage prospects with a good dowery.

While I generally disagree with Beauvoir’s ideas, I can understand from the broad strokes of her life how she traveled the road she did. While lived experience is one of the most important and lasting teachers in our lives, it can also blind us to broader perspectives. As a species that instinctively tries to find order in chaos, we also tend to see our experiences of examples of what is normal or universal, rather than of a specific variation on a more common general experience. That’s especially easy to do if our own experiences are common to the people we know. I can appreciate that Beauvoir would have understood the role her mother played and that the nuns prepared her for to be undesirable and limiting. She also spent most of the first half of her life in a country that was either occupied or recovering from occupation–a political and economic reality that is not conducive to a happy family life.

So, somewhat understanding why Beauvoir wrote what she wrote, I would like to present a different perspective. I would say that, in Judaism, “washing up saucepans” is absolutely part of a “divine mission,” not just for women, but for everyone. Torah spends a lot of time on the importance of cleanliness, both physical and ritual. We are to keep our bodies clean and do our best to prevent the spread of contagion. We are to avoid contact with the dead, carcasses of animals that have not been properly slaughtered, and bodily fluids of various types. Not only are we supposed to keep our bodies clean, but we are also supposed to keep clean from those same things our homes and belongings. Every year, we start the first month by clearing, not just our homes, but the land of things that are fermented and the starters used to ferment them. The remedy for uncleanliness always involves washing yourself and whatever you might have contaminated and/or destroying things that cannot be cleansed.

Torah repeatedly tells us that being physically clean is an important part of being holy. Indeed, it deliberately blurs the lines between the two. Distinguishing between the common and the sacred involves distinguishing between clean and unclean. We are to make ourselves clean anytime we wish to or must participate in ritual life or if we want to interact with those who have already made themselves clean. At the end of the day, obeying ritual requirements, acting in good faith towards others, and obeying the laws of cleanliness come together to describe how we maintain ourselves as a holy people.

Being clean and keeping our homes clean are vital parts of our “divine mission,” if you will. What is important, though, is that the mission of cleaning up is not limited to women. It applies to everyone. There are requirements that apply to one group and to others. Laws about the priests apply to the priests. Laws about Nazarites apply to Nazarites. Laws about lepers apply to lepers. Not surprisingly, the law about nocturnal emissions applies to men, and laws concerning menstruation and childbirth apply primarily to women. Outside of laws like those, most cleanliness laws are universal in application. Cleaning things isn’t just how women fulfill religious obligations; it’s part of how everyone does.

The thing is that, while not exciting, being clean and maintaining a clean living space are important parts of being healthy, both physically and mentally. Being clean and existing in a clean space are part of it, but the act of cleaning, that discipline, is also good for both body and mind. Cleanliness and mental health are so closely connected that the lack of adequate hygiene, a compulsion to clean, an obsession with whether things are clean, or a fear of cleaning are all considered symptoms of mental illness or distress in the secular world. It is an obligation we owe ourselves just as much as a requirement of religious devotion.

As much as we each individually might not want to do the cleaning on any given day, the temptation to shove all of it off on a particular class of people is unhealthy. Since Torah requires that we have one law for everyone, rich and poor, native born and foreigner, man and woman, we cannot say that doing the washing is a woman’s purview. Instead, we can say with confidence that washing things, including saucepans, is a vital part of everyone’s divine mission. Going beyond that, we bring meaning to life and harmony to our homes and communities when we have the discipline to recognize the inherent value in the mundane aspects of daily life and participate in those aspects willingly and diligently.

Throughout Torah, we are repeatedly told that we should do or not do things in order to be “a holy people to HaShem.” In Devarim, we are told that committing to Torah and all its statutes makes us a “holy people.” Living a clean life, in which we acknowledge the inevitability of uncleanliness and respect the work necessary to become clean again are just as important to being righteous as living with a clean conscience. “Washing saucepans” is part of the “divine mission,” and don’t let anyone tell you differently.