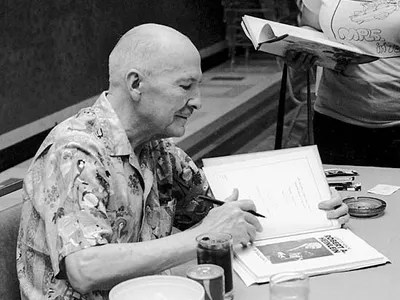

Today, I came across this quote from the famous science fiction author Robert Heinlein (1907-1988):

“The Ten Commandments are for lame brains. The first five are solely for the benefit of the priests and the powers that be; the second five are half truths, neither complete nor adequate.”

Taken strictly at face value, I can kind of see where he’s coming from. Life is too complex, too nuanced, to be summed up in ten rules that have no context, no explanation, and no structure. Whether you are Jewish, Samaritan, or Christian, scripture is not limited to the Decalogue, and any religion that tried to do so would soon be found insufficient. That’s because seeing the Decalogue as the basis of moral law is backwards.

Instead, the Ten Commandments are more of a mnemonic device–shorthand to help the average person remember the basic premise and underlying principles of the various laws enshrined in Torah. Many years ago, I read a wonderful book by Hermann Wouk, entitled This Is My God, and one of the most memorable points made in that book is that the most remarkable thing about the Jewish People is that we are a nation defined and attached first to a book and second to a place. Other nations are founded in relation to a place first and tend to dissolve when removed from that place, but Torah itself is the story of a people who had to become a coherent nation, centered on a book, before they could develop a geographical identity. That book (or set of books, rather) is Torah, which is the portable cultural and national identity of a people that has persisted for milennia. It contains an “origin story,” if you will, a mythology, a system of religious practice and belief, a history that includes both national narrative and relationships with the other peoples of the region, an overarching purpose/mission, government and judicial structures, cultural norms, and a legal code flexible enough to encompass tribal, monarchical, and electoral governance.

The first couple of commandments in the Decalogue establish monotheism centered on Hashem. Yes, that does benefit the priests. Heinlein was right about that, but misses the point. Edmund Burke argued that monarchy was necessary to England, because English Common Law essentially consists of addenda to the Magna Carta, which is a contract establishing rights and obligations between the English monarch and his people. In the absence of the king, the entire legal system falls apart, because the contract that predicates it has been removed. Torah is similar, in that it is an agreement (a contract) between Hashem and the Jewish People stating that He will provide prosperity and protection so long as the people follow a set of laws and worship Hashem exclusively. As soon as that exclusivity is set aside, none of the other rules are enforcible.

After establishing Hashem as the G-d of Israel and forbidding idolatry, the Decalogue forbids swearing falsely in G-d’s Name. Now, Heinlein was raised in what he referred to as the “Bible Belt” in Missouri, in the first half of the twentieth century. In that time and place, he would have been taught that saying things like, “Oh, my g-d!” or “G-d damnit!” were violations of that commandment. Taken with the quote above, his implication is that the commandment seeks to limit a relationship with Hashem to the priests. Taken in the context of the TaNaKh, however, that this prohibition is about invoking the Name of G-d when swearing to do or not do something. Now, in many biblical instances describing people making oaths, that is done in front of a priest as a witness, so that does reinforce the priestly role, I suppose, but priests aren’t the only people who can bear witness to oaths, which the narrative also attests. However, that’s not the point of the exercise. The purpose of this commandment is not the proper procedure of swearing, but the prohibition against making a sacred oath and then breaking it, either deliberately or through negligence.

Even if you are not a religious person, I think we can all agree that people should keep their promises. They should especially keep their promises when those promises take the form of a contract, which is essentially what an oath is. Friendships, marriages, families, and society as a whole all work better when people both deliver on their promises and take it very seriously when people break those promises. The notion that formalized promises (oaths, contracts, whatever you want to call them) are legally binding is a pretty common value across cultures and throughout history. You cannot have a coherent civilization if its members can’t trust each other on some baseline level.

The law establishing Shabbat also benefits the priests, but it establishes the importance of rest, study, and introspection as well. It safeguards the mental health of the common man and is as much a labor law as it is anything else. Since we aren’t supposed to make our animals work on Shabbat either, it also establishes a baseline prohibition against animal cruelty (overworking one’s animals). You don’t see that if you are only reading the Decalogue, though. You see that in the multitude of other places in Torah that go into the specifics of observing Shabbat.

Assuming that Heinlein was referring to the Philonic counting of the Ten Commandments, which is pretty common in Christianity, the fifth commandment in his statement says to honor your parents. In English, this commandment is often translated as obeying one’s parents, and that’s probably how he was taught it. That take lacks the nuance necessary to be useful or functional. Parents aren’t always honorable people who should be obeyed, and Jewish interpretations often say that this is about parents teaching tradition to their children. The story of Yonatan siding with David over his father, King Shaul, is a famous example of a son righteously disobeying his father.

The commandment natural correlary to the exhortation that parents raise their children “in the way they should go.” Edmund Burke summed the notion up nicely when he argued that every generation owes its successors a functional tradition. If your parents are living correctly and have taught you how to live correctly, you have an obligation to continue in the same vein. Now, I would add to that the observation that children of unrighteous parents have and obligation to turn to a better path. When they do, they bring honor to their parents, regardless of whether their parents deserve it. Indeed, we should all honor our parents by striving to be better than they were.

However, in most of recorded history, property and wealth were held by families, not individuals. And, in most cases, older family members (often in extended families) had more authority and responsibility over that property than younger family members. Modern Westerners, especially Americans, tend to think in very individualistic terms, but if we use more collective, more archaic understandings of family, property, and wealth, this commandment also suggests that we shouldn’t undermine the financial plans of our parents or the family reputation. This commandment does not contradict the instruction found repeatedly throughout Torah not to pervert justice in favor of anyone.

The remaining five commandments are fairly straightforward: no murder, adultery, theft, perjury, or coveting. In general, these are also requirements for a cohesive society. It gets right back to the necessity of trust in any cooperative endeavor. Heinlein was probably taught that the commandment against murder was against killing in general, which is, again, lacking in nuance and specificity. The English word “murder” is derived from a word meaning “to kill in secret.” The relevant Hebrew word has to do with “killing in hate.” They aren’t precisely the same concepts, but both indicate killing without official permission or authorization. Indeed, Torah uses that very word when describing how the “avenger of blood” is authorized to kill the manslaughterer who leaves his sanctuary city prematurely. Either way, the deliberate taking of human life must be limited to those sentenced to die by a just court, and Torah, again, provides guidelines to help ensure that such sentences are correct.

Everything else pretty much falls under the category of acting in bad faith. Not abiding by the requirements of your marriage or respecting the marriages of others is acting in bad faith and undermines the larger social contract. Theft is the basic definition of dealing in bad faith, and Torah discusses different kinds of theft and fraud at length, ranging from actively stealing goods or animals to defrauding customers, to entering marriages under false pretenses. I think most people would agree that all those things destroy public trust.

Likewise, perjury undermines any type of justice system. Again, Heinlein might have been working with an overly simplistic understanding of this commandment, since it is often taught among Christians as a commandment against lying in general. Unfailing honesty isn’t always a good thing. And while being honest is generally good, most lies do not rise to the level of offering false testimony in court or pressing false charges.

Finally, covetousness has to do with the conspiracy to commit a crime. Here, again, the perspective that Heinlein was probably raised with would have been more expansive, including the admiration of anything that isn’t yours and possibly even the paying of compliments. As with other commonly made over-generalizations, the lack of specificity in interpretation is what makes the commandment less than useful. Taken in the larger contexts of Torah and the rest of the TaNaKh, it’s actually a pretty useful rule.

There’s a famous Talmudic story that a Roman man went to the sages Shammai and Hillel and presented each of them with the bet that he would convert to Judaism if they could teach him Torah while he balanced on one foot. Shammai chased the man away, but Hillel told him, “That which is hateful to you, do not do to others. That is the whole Torah. The rest is interpretation. Now, go study.” A variation of this summation is also included in Christian scriptures, and it’s a reasonably fair observation.

We can think of the exercise at hand as a discussion of a taxonomy. In biology, living things are divided into a series of groups of increasing complexity and specificity. Hillel’s statement–the most basic, least nuanced boiling down of Torah possible–is like the Kingdom at the top of the taxonomy. To say that bears fall within the animal kingdom is true, but not useful in defining what a bear is. Likewise, Hillel’s statement is true, but has limited usefulness, especially if creating a cohesive society is part of the goal.

The Ten Commandments are similar to the next division down, Phylum. Again, bears are members of the phylum chordata (they have spinal chords), which is good for distinguishing them from insects or jellyfish, but still not very useful in a practical sense. Then we get to Torah itself, which actually gives us nuanced information that informs us on how to live out “not doing things we wouldn’t want done to us” in terms of how to carry out the Decalogue, just as knowing that bears are part of the mammalian order is actually useful in narrowing down what distinguishes them from all other life on Earth.

We can learn more about good behavior in practice from the Neviim and Kethuvim, which provide us with case studies and commentaries, in addition to histories and stories. Similarly, taxonomic class tells us that bears are carnivores. You can then continue getting more specific in how to enact Torah in increasingly specific circumstances, using commentaries and traditions, just as you can continue narrowing down what a bear is, based on ever more minute distinctions, through the classifications of family, genus, and species.

However you handle the specific laws of Torah and their application to real world scenarios in the modern day, the fact remains that you can sort them into the broader categories of the Decalogue. Likewise, when confronted with a novel situation, you can compare your potential responses to the concepts covered in the Ten Commandments to narrow down potentially ethical courses of action.

Do the first five commandments serve to empower an established hierarchy? Yes. Part of having a coherent cultural and national identity involves defined power structures. A huge part of that power structure in Judaism is the covenant between Hashem and His people, and the first three commandments are broadly how we demonstrate that we are still participating in that exclusive contract with Hashem. If the covenant is in effect, then the remaining commandments follow.

Are the remaining five commandments inadequate as a moral guide? Also yes. They are the Cliff’s Notes version–a mnemonic to help us remember a much larger legal codex, but also section headings into which all those more specific behavior rules and criminal codes fit.

Are the Ten Commandments for “Lame Brains”? I don’t think so. Things that are truly stupid usually don’t have that kind of staying power or capture the human imagination the way the Decalogue has across cultures, languages, religions, and national identities for milennia. And the fact is that these kinds of general rules have been found necessary in most civilizations, in one way or another, in order to maintain social order and trust. Not stealing or engaging in extrajudicial killings, abiding by marital contracts, having a reliable and honest judicial process, and avoiding conspiring to take other people’s stuff are pretty basic and universal social rules, even if they have been very imperfectly followed throughout history and define their terms differently from one culture to the next. You can arrive at their necessity without any kind of religious conviction through logical deduction and a little honest observation of human behavior.

Robert Heinlein lived in a time when the world was being turned on its head. Rules that made sense in previous generations stopped being sufficient without explanation. Heinlein was an iconoclast in iconoclastic times. Like so many of his ilk, he threw the proverbial baby out with the bathwater, largely because he couldn’t or wouldn’t separate his own experiences from an honest appraisal of cultural mores. Such men are necessary to society, because they call out hypocrisy and faulty logic, but they must also be held to the same standard of being called out for their own faults.